Educational Stories

This page has a variety of true stories with a wide

variety due to my broad definition of education

as learning from life-experiences.

Monday vs Tuesday - Cliffs Notes - Welding - Skiing)

plus The Joys of Science (it's fun to solve mysteries),

and Aesop's Activities for Goal-Directed Education,

and Actively Learning by Exploring & from Others.

iou – Many stories are in rough form, awaiting revision,

but a page about my new home in Madison has stories

(about colors of seasons, temperature expectations,

seeing wind by watching snow, two wonderful dogs,

the brilliance of NBA play-ins, [...continued in June])

that are more well-developed and polished.

plus an expansion/revision of these Table of Contents.

Also (iou) I'm beginning to write other stories, about...

exploring your own city (inspired by returning from Europe),

taking time to watch snow [and "see wind"] in March 2012

and earlier snows in my first city (the home of my first UW),

psychology of teaching children (or dogs) instead of adults,

my respect for defenssive halfbacks (inspired by my playing),

and much more – with "educational" very broadly defined.

Understanding and Respect

Students in my high school learned valuable lessons about accurate understanding and respectful attitudes from one my favorite teachers. Although he was a skillful lecturer, the special feature of his civics class was its debates. On Monday he convinced us that "his side of the issue" was correct, but on Tuesday he made the other side look just as good. After awhile we learned that, in order to get accurate understanding, we should get the best information and arguments that all sides of an issue can claim as support. After we did this and we understood more accurately & thoroughly, we usually recognized that even when we have valid reasons for preferring one position, people on other sides of an issue may also have good reasons, both intellectual and ethical, for believing as they do, so we learned respectful attitudes. {thinking with empathy and kindness}

But respect does not require agreement. You can respect someone and their views, yet criticize their views, which you have evaluated based on evidence, logic, and values. The intention of our teacher, and the conclusion of his students, was not a postmodern relativism. The goal was a rational exploration and evaluation of ideas in a search for truth. {more about his teaching and respectful non-pomo evaluation}

A “Cliffs Notes” Approach

This section explains how — in three decisions and a library — I recognized the similarity between Cliffs Notes and the introductory levels of my websites.

The first two decisions were easy. Yes, I would watch the movies. No, I would not read the books. In either form, in movies or books, Lord of the Rings is a classic. Although I would enjoy reading the trilogy by Tolkien, "time is the stuff life is made of" (said Ben Franklin) and I decided that reading three large books would not be a good use of my time. But reading one small booklet would be quick and useful, so I decided to read the summary/analysis written by Gene Hardy for Cliffs Notes. And having an introductory overview of “the big picture” — provided by Hardy's summary of the three books — helped me understand and enjoy the three movies. {* the five-day conference, Dec-Jan of 2002-03 in Atlanta, was "Following Christ" organized by Intervarsity Christian Fellowship}

In the two weeks between seeing the first movie (on DVD) and second movie (in theater) I attended a conference that had a book table filled with high-quality books. While reading the back covers, table of contents, and occasional pages, I thought about the many fascinating ideas I would miss because I wouldn't be able to invest the time needed to read these books. I also was thinking about Lord of the Rings and the practical educational value of reading one small book instead of three large books, and I made the connection between booktable and website. It would be useful for me to have a condensation containing the distilled essence of important ideas from books on the table, and giving you "a condensation containing the distilled essence of important ideas" is the goal of the introductory summary-pages in this website. { two examples: for Whole-Person Education & Problem-Solving Education }

Learning from Experience (how to excel at welding or...)

One of the most powerful master skills is knowing how to learn. The ability to learn can itself be learned, as illustrated by a friend in Seattle who had an unusual strategy for work and play. He worked for awhile at a high-paying job and saved money, then “took a vacation” so he was free to wake when he wanted, read a book, hang out at a coffee shop, go for a walk, or travel to faraway places by hopping on a plane or driving away in his car.

Employers usually want workers who are committed to long-term stability, so why did they tolerate his unusual behavior? He was reliable, always showed up on time, and gave them a week's notice before departing. But the main reason for their tolerance was the quality of his work. He was one of the best welders in the city, performing a valuable service that was in high demand and doing it well. He could audition for a job, saying “give me a really tough welding challenge and I'll show you how good I am.” They did, he did, and they hired him.

How did he become such a good welder? He had "learned how to learn" by following the wise advice of his teacher: Every time you do a welding job, do it better than the time before (by learning from the past and concentrating in the present) and always be alertly aware of what you're doing now (and how this is affecting the quality of welding) so you can do it better the next time (intentionally learn from the present to prepare for the future). This is a good way to improve the quality of whatever you do. Always ask, "What have I learned in the past that will help me now, and what can I learn now that will help me in the future?", while concentrating on quality of thinking-and-action in the present.

an update: After I originally wrote this, much later I thought more carefully about how we should try to effectively regulate our metacognition (thinking about our thinking), and the "always ask" became "sometimes ask", as explained in Learning From Experience to improve your Learning and/or Performing (and/or Enjoying) which includes a revised-and-expanded version of this true story.

How I Didn't Learn to Ski

(by Learning from Mistakes)

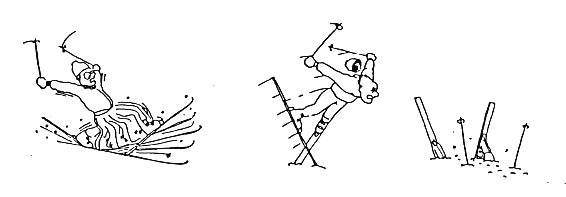

My first day of skiing! I'm excited, but the rental skis worry me. They look much too long, maybe uncontrollable? On the slope, fears come true quickly and I've lost control, roaring down the slope yelling "Get out of my way! I can't stop!" But soon I do stop — flying through the air sideways, a floundering spin, a mighty bellyflop in icy snow. My boot bindings grip like claws that won't release their captive, and the impact twists my body into a painful pretzel. Several zoom-and-crash cycles later I'm dazed, in a motionless heap at the foot of the mountain, wondering what I'm doing, why, and if I dare to try again.

Even the ropetow brings disaster. I fall down and wallow in the snow, pinned in place by my huge skis, and the embarrassing dogpile begins, as skiers coming up the ropetow are, like dominoes in a line, toppled by my sprawling carcass. Gosh, it sure is fun to ski.

With time, some things improve. After the first humorous (for onlookers) and terrifying (for me) trip down the mountain, my bindings are adjusted so I can bellyflop safely. And I develop a strategy of "leap and hit the ground rolling" to decrease ropetow humiliation. But my skiing doesn't get much better so – wet and cold, tired and discouraged – I retreat to the safety of the lodge.

The lodge break is wonderful, just what I need for recovery. An hour later, after a nutritious lunch topped off with delicious hot chocolate, I'm sitting near the fireplace in warm dry clothes, feeling happy and adventurous again. A friend tells me about another slope (St. Moritz) that can be reached by a scenic chairlift (Panorama Gondola), and I decide to "go for it."

This time the ride up the mountain is exhilarating. Instead of causing a ropetow domino dogpile, the lift carries me high above the earth like a great soaring bird. Soon, during a slow traverse – moving horizontally across the hill, in control – I dare to experiment, and my new experience inspires an INSIGHT ! If I press my ski edges against the snow a certain way, they “dig in” and this, combined with unweighting (a jump-a-little and swing-the-skis-around foot movement) produces a crude parallel turn that lets me zig-zag down the slope in control, without runaway speed, and suddenly I can ski !

Continuing practice now brings rapidly improving skill, with my “level of success” increasing, and by day's end I'm feeling great. I still fall down occasionally, but not often, and I'm learning from everything that happens, both good and bad. This progress produces a confident hope that even better downhill runs await me in the future. Skiing has become fun! 🙂

How I Didn't Learn to Ski (by Making Mistakes),

and then Did Learn to Ski (by Doing it Correctly):

During my morning failures, I did not learn by MAKING MISTAKES. In the afternoon, I did learn from SUCCESS, after an INSIGHTFUL DISCOVERY let me use QUALITY PRACTICE – with SUCCESSFUL SKIING – to gain QUALITY EXPERIENCE, and learning from these experiences led to rapid improving. Of course my success wasn't perfection, but (as explained above) I was "learning from everything that happened, both good and bad" by using feedback from partial success to let my body learn how to adjust-and-improve. / also: Instead of giving up after my unpleasant morning disasters, with PERSEVERANCE I tried again, and with FLEXIBILITY I did it “different and better” in the afternoon.

ski lengths: For my morning runs on the main slope of Mammoth Mountain (in front of its lodge), they gave me skis (200 cm, 6' 7")* that "looked much too long," were taller than me. Then for my afternoon runs – after I told them about my “uncontrollable” feelings – they gave me skis that were shorter, 190 cm. But these still were much longer (and thus more difficult to control) than current recommendations of 162 cm to 168 cm.

more: In a “deeper examination” page, these experiences are used to illustrate two principles for learning — Insight & Quality Practice, plus Perseverance & Flexibility — and to examine these principles in more depth. { btw, the clever cartoon is by Frank Clark, not me }

more: In addition to my process of skills-learning that was one day for skiing (with morning failure followed by afternoon success), other stories explain why my process-of-learning was long for juggling (12 years & 45 minutes) but short for swimming (5 seconds). Also, why our dog danced with joy twice each day.

And with an "X Games" cousin of snow skiing, barefoot water skiing.

Dogs – Role Models for Joy and Gratitude

Like most dogs, our Zoë was for us (and still is for others) enthusiastically fun-and-loving, a good role model for joy-and-gratitude. Life would be better if more people were more fun-and-loving!

Zoe as a Facilitator of Joy: In their attitude & actions, dogs can inspire people to be more joyful. For example, during the 4 months when we visited Mom almost daily in a living facility, Zoe met many people and greeted them with enthusiastic joy, usually by standing up and “dog paddling” for them. Most people would respond joyfully to her; then when they interacted with me, their joy (due to Zoe) would help our interactions be more joyful and better, because all of us (Zoe, them, me) were in a joyful mood. In this way, she was a facilitator of joy. A friend from church said “Zoe is a good role model for attitudes-and-actions we all should have, joyfully celebrating life, enthusiastically sharing our joy with others.” Yes, in Greek her name means “life” and she is full of life! {although with Zoe – and many other dogs – the enthusiasm is obvious, during our person-to-person interactions the enthusiastic joy is usually expressed in ways that are more subtle, but are real, and can be recognized by others.} { joy and play: in one of Zoe's videos – it's in YouTube along with my juggling video – she isn't the focus, instead the stars are playful grandchildren who were inspired by her dog paddling. } { why did our dog-before-Zoe dance with “no more pain” joy – twice each day? and how did he demonstrate, with his generous forgiving, another way that dogs are good role models for us? }

The Most Intelligent Sport

I confidently claim that football is the most intelligence-requiring sport, in its planning of strategies (at the levels of a team & its individuals) for the battles of offense versus defense that occur every play, and for an overall 4-quarter game. Every position has its own mental challenges, requiring unique kinds of experience-based knowledge and fast real-time responding, but being football-smart is especially important for coaches and quarterbacks. The coaches & players who want to “be their best” decide to invest many hours watching films of opponents (and themselves), analyzing what has happened and imagining what might happen, planning their strategies for what they will do, and how they will respond to the counter-strategies of their opponents, by logically-and-creatively imagining possibilities, by asking “what are they thinking?” and “what do they think we're thinking, and how should this affect our own thinking & deciding?” and “what do they think we're thinking about their thinking?” and so on.

Learning Respect for Defensive Backs

I have lots of spectator experience with football. My limited playing experience began with playgrounds in small-town Iowa, and ended with flag football at UC Irvine where in my senior year I played for the Chem Grads who included a future Nobel Laureate. They were a great team, and I played a small part in helping us win the intramural campus championship. They let me play defensive back, and I did it fairly well, catching about as many passes as the offensive players I was guarding, but this high ratio – of (my interceptions / their receptions) – was mainly due to the relatively low levels of preparation-and-skill of our opponents' receivers & quarterbacks. With appropriate humility, I realized then (and now) that if they had played at a higher level – so they were more capable of exploiting my vulnerabilities – my results would have been much worse. And that's why I learned to respect defensive backs (who play in high school thru NFL) when they can successfully cope with the tough challenges of defending against pass-catchers & pass-throwers who are highly skilled (physical & mental) and have clever offensive strategies.

Our team had three Defensive Backs. The other two were more experienced and football-smart, so each was responsible for making real-time decisions about “who they would cover” – or if instead he should defend against a run – in complex situations that changed for every play (like a receiver emerging from the other team's offensive backfield) or when it was a run instead of a pass. By contrast, my job was simple; usually I did the same thing every play, guarding the other team's top receiver. One of these DB's (smart and fast) usually took another receiver, while the other (smart but less fast) played the role of a linebacker who sometimes played pass defense. But sometimes the other DB's exchanged roles; basically they just cooperatively improvised by planning-and-doing whatever seemed best in each situation.

During our pre-season practices I was educated and humbled. I was taught some defensive strategies, like the concept of “playing center field” when the football is thrown to another receiver (not the one I'm defending) by running to where the ball will come down, like a center fielder chasing a baseball. But mainly I was challenged – and humbled – by playing against the offense of Chem Grads, trying to guard the league's best receiver, running cleverly planned routes, catching passes thrown accurately by the league's best quarterback. I didn't do well against this combination, but I was challenged, and this helped me learn and improve. Compared with these practices, our games were much easier because the other team's combination — especially the quarterback (usually the most important player on a team, the biggest difference-maker in most games) but also the receiver — were less skillful, were not the league's best.

But they were reasonably skillful and I was inexperienced, so I kept imagining the worst possible outcomes, thinking about “what they could do” (e.g. if they did “this fake” followed by “that move”) – to escape from me,* and maybe even get my legs twisted up so I fell down – by using clever plays and tricky fakes. For example, the receiver might be running in one direction, then suddenly change to running in another direction; the offensive player knows what he is planning and where he will go (but the defensive player doesn't) and this knowledge is a huge advantage. But usually my worries didn't happen (the escapes were rare, and I never fell) but this was mainly because they didn't plan well — with clever plays & fakes, like those described in this analysis — and the quarterbacks were not skillful enough to take advantage of the times when I didn't closely cover my receiver, *so instead of cleverly escaping for a touchdown the result often was like this jumping interception. / One example is a game where in the first play I realized “uh-oh, this guy is faster than me,” significantly faster. But somehow they never took advantage of the difference in our speeds, like by doing button-hooks with two options, so if I “give him space with loose coverage” he catches a short pass, but if I “cover him closely” he runs away from me and gets enough separation to catch a long pass. Of course, this strategy assumes the QB has enough accuracy (but he didn't) to take advantage of the separation allowed by the receiver's speed. But they didn't do these things, and I survived the afternoon without humiliation. In fact, during their second offensive series I jumped high into the air to intercept a pass, and I could feel my knee accidentally hit his face. {so his experience was less fun than mine} During the game, his superior speed could have given his team a big advantage, but they didn't take advantage of it, because they had inferior strategies (in running routes) and skill (throwing the ball).

These experiences gave me a high level of respect for defensive backs (cornerback, safety, linebacker) at all levels (high school, college, professional) who play against teams with clever strategies (planned by coaches, quarterbacks, receivers) and skillful quarterbacks who are accurate throwers, who coordinate well with their skillful receivers. Now when I watch football on TV, I closely watch the replays when they show offense-vs-defense in passing patterns, instead of the camera focusing on the QB as it does in their real-time initial showing of every play. And in addition to not being victimized by clever plays & fakes in a simple man-to-man defense (like I was playing), every defensive back must be football-smart by knowing how to effectively play their own part (in cooperation with other DB's & linebackers) when their team is using a zone defense.

Our closest game was against a team with rugby players.* After their first play — a kickoff return using a line with multiple laterals (video) like a Quadruple Option Play — again I thought “uh-oh, we're in trouble.” But their unusual-and-skillful offense didn't overwhelm our defense, and we won 13-6. I was responsible for 2 of the 3 touchdowns, one for them and one for us. Huh? First, during one play I should have “played the receiver by staying close to him” but instead I “played the ball” and mis-judged it, letting it fly over my head, where the receiver caught it and scored. Oops. Later I intercepted a pass, and my flag would have been taken by their QB (Stu Bonner, one of the best athletes at UCI) but I heard our football-smart DB say “wait Craig, let me block him” so I waited, he blocked, and I scored. We scored one other touchown, and (despite their rugby offense) they didn't, so we won! This final result – plus my touchdown – let me feel a huge sense of relief, because we didn't lose the game due to my touchdown-allowing mistake. {it was my only "big oops" of the year, with only one TD allowed} / * After winning our division in this 13-6 game, we won the two-division campus championship 52-0.

One member of our team, the Chem Grads, was Professor Sherwood Rowland who later was awarded a Nobel Prize for his work on ozone depletion in the upper atmosphere; in football he was a lineman, and I thought “for an old man with a nickname ‘Sherry’ he sure is a tough dude.” {he was 42, which seemed old when I was 21, but of course 42 seems young now, when I'm 74} Our team had many highly skilled players, including Steve (quarterback - smart, elusive, accurate) and Pat Carroll (a star receiver in high school) and... [[ iou - later I'll complete this sentence or will delete it. ]]

Watching a Linebacker

One of my favorite “live games” was at small-school Humboldt State University in far-northwest California, where I watched a linebacker who was running all over the field – forward & backward, left & right – making tackles on many plays, always seeming to be in the right place at the right time. Maybe just listening to the announcer – often saying “tackle by Smith” – would have alerted me to his activity. But I was even more aware of the linebacker because the previous day I had met him at the beach where he (and other players) was fishing (and he was from Huntington Beach, close to where I've lived in Orange County, CA) so I was “watching him” during the game, in one of my favorite football-watching experiences.

Why the NIL-and-Portal exists,

how it's ruining college football,

and (maybe) some ways to fix it.

an update: This page was written in early 2023, and a recent agreement (May 2024) has changed things.

iou – Below is an outline that will continue being developed & revised, maybe in late 2024.

illogical policies: Many decisions and non-decisions have led to actions that are unfair. One example is forcing players to make portal decisions immediately after

Originally the following paragraph was last, but now it's first.

a solution: Maybe (but not certainly or even probably, because I haven't yet studied this) the NCAA – in cooperation with schools – could develop some kind of SALARY CAP for each team, similar to what's used in pro sports like NFL and NBA. Maybe. Hopefully. Or they'll design a better solution. NCAA made huge mistakes early, by not "thinking ahead" and making policies and rules-with-penalties. Consistent with the principle that "to catch a thief you should think like a thief," first they should have thought about all the ways a scheming fan (or school) could use the NIL-and-Portal in ways that would be selfishly beneficial for their school but would damage the sport as a whole. Second, they design policies to prevent (or minimize) the scheming, to reduce the damage. Of course, NCAA also wants to avoid costly lawsuits, but with intelligent strategies they could have (and still can) design ways to maximize the positive effects of their policies, and minimize the chances of having negative effects, including lawsuits. { iou – soon I'll learn more by hearing videos & reading pages; then my "maybe" could change to "probably" or to "probably not, unfortunately".}

history, Part 1: Every year, huge amounts of money are made by college football. It goes to companies (television & radio, makers of sports equipment,...) & colleges & NCAA, plus coaches, but very little to players. (usually only tuition, food & lodging,...) Therefore, in the past many people have wanted to develop a system for paying players. [[ disclaimer: I'm not certain about the correctness of the following ideas, but think they're basically correct -- soon I'll learn more, and new knowledge either will confirm what I'm saying or I'll revise it so it matches the facts. ]] An egalitarian way to do this – like by paying all players a reasonable amount – was hindered by Title 9, requiring that things be equal for athletes who are male & female, and thus in minor sports (where most women compete) & major sports (mostly men). Due to this restriction, the main money-making sports (especially men's football, but also men's basketball) could not have the only athletes being paid, instead it had to be distributed to all athletes, including those in minor sports; but this would put financial burdens on schools, if they had to pay all athletes (men & women, major & minor) the same amounts. So this egalitarian solution (with all athletes getting similar amounts) was economically impractical. More specifically, this meant that a football team could not pay all players the same; they could not even develop a system where some positions (e.g. quarterbacks) were paid more, and starters were paid more.

history, Part 2: Everything changed on June 21, 2021, when the US Supreme Court decided (unanimously, 9-0)* that players must be allowed to receive payments for using their "Name, Image, Likeness" (NIL) so the NCAA was forced to allow this. And I think NCAA was not allowed to (or decided not to, wanting to avoid costly legal challenges) place reasonable rules on payments of NIL. NCAA also decided (I'm not sure why, but will investigate in the near future) to allow a "free portal" so all players could become "free agents". / When I first learned about this decision (recently, in December) I thought "it's the current conservative majority, deciding based on laissez fair hands-off philosophy" but it was 9-0 so evidently the main factors were legal principles, not political-philosophical preferences.

the portal: I think a portal is useful-and-wise for quarterbacks where typically there is only one per team – because "if you have two quarterbacks, you have none" is the usual thinking of coaches – but not for players in positions where there is flexibility. This flexibility occurs because an athlete with certain abilities (re: their athleticism, preferences, experiences) can move to another position if their preferred position is occupied by another player; e.g. a pass-defender could be a cornerback, safety, linebacker (defensive) or (offensive) a wide receiver, tight end, running back; or a lineman could be offense or defense, at center-guard-tackle-end, or a linebacker. And they can be first string (playing most downs) or second string (playing many downs, with opportunities to "show what they can do" impressively, and move up to first string). But these flexibilities are impossible (or at least impractical) when most coaches decide their strategy for quarterback; usually they decide "one QB, playing all downs" so a second-stringer (even if they have a lot of talent) may get stuck in a situation where a talented QB won't get a chance to play (for pleasure & glory), and "show what they can do" for a possible career in NFL.

the results: The combination of NIL (basically with no rules about "how much money" and "how payments are made") plus portal — where any player can say "I want to be a free agent" so they can "sell their services to the highest bidder" in a high-stakes auction with many schools bidding against each other — has produced a "wild, wild west" situation where there are no rules. And the customary recruiting strategies — by persuading a player to join your team because they like the coaches, think the coaches can help them develop their skills, hope to compete successfully (to win a championship for their league or nationally, or at least win most games), and maybe make it to the NFL so they can get paid, like the school's location & atmosphere — will no longer be the main factors in making a decision. A player can get huge amounts of money NOW – not having to wait for pro football (unlikely for most, even with talent) – and for most players this will be a major factor (maybe the most important) in their decision about joining a team.

timings: Some of these effects happened in Fall 2021, and more in 2022 when there could have been a MAJOR effect if USC (probably the most skillful in quickly taking advantage of NIL+Portal) had won the Pac-12, instead of being defeated in their league championship. The effects will increase dramatically for Fall 2023. This already has begun, with MANY players deciding to enter the portal, to become free agents who will play for the school that will pay them the most money. In many cases, the money they'll make is more than they could make in professional football, even if they survive injuries and if they play well enough to make it into the NFL, and neither "if" is guaranteed. Instead they can make huge amounts of money immediately, fully guaranteed.

timings: Due to extremely stupid decisions by NCAA, the portal opens for most teams (those not in the playoff, CFP) before the CFP begins, and before many other teams play bowl games. Therefore (because it's in their best interests) players usually make decisions EARLY in the portal's open period, often BEFORE their teams play a bowl game, and occasionaly before they play their CFP games.

more information: Soon I'll find more-and-better links (to videos & pages) where you can quickly learn from experts who know much more about it, compared with me. Some videos: from fans of Ohio State - and with link-pages (because I haven't yet listened & made decisions to choose "the best" for you) college football being ruined - fixing NIL-plus-Portal (is this possible?) - effects for Alabama - benefits for USC - histories of NIL & Portal - and more later, with selectivity (by me) by linking to specific videos instead of just to link-pages that list multiple videos. And I'll look for some good web-pages.

Here are two related topics, that will be developed later:

history of Olympics: e.g. the unfairness of USSR (who were allowed to pay athletes to be in the Soviet Army where their only job was to play hockey) versus countries like USA who could only use all-star teams of college athletes, so it was like NCAA Champion (USA) versus NHL Champion (USSR); plus historical un-fairness like Jim Thorpe, or (lesser known) Wes Santee who almost ran The First Four-Minute Mile.

QB's and salary caps: NFL quarterbacks usually take a very high percent of the money their team is allowed (by the salary cap) to pay the entire team, so the QB is taking their multi-millions from teammates, not from the owners. I wish star QB's would decide, more often, "I have enough money – i.e. more than I'll be able to spend during the rest of my life – but I want more wins, and maybe a championship" so, logically, "I'll take less money so the team can spend it (the excess that I'm not getting) on other players, so we'll have a better team and better chances to win." Occasionally a star-QB will decide to take less money than they could demand, but it's rare, and I wish this would happen more often. / And I think the NFL — with enthusiastic support from the player's union, who should be representing the best interests of ALL players, not just the few stars who now are gobbling up most of their team's salary — should set an upper limit. e.g., NFL could require that no player (like a QB) can make more than 5% of the entire salary – for 2023 this 5% would be $11 million, and a QB could survive on this – and maybe have other kinds of limits on how a team is allowed to spend its total salary-capped amount. This would prevent a team from being held hostage by a greedy star who says "pay me or I'll leave" even though the decision makers – the Owner(s) & General Manager – would like to "spread the wealth" among more of its players.

What is the toughest skill in sports?

As a spectator, my favorite kind of player is point guards. In part it's the art, but also appreciation of skills.

What is the most difficult challenge in sports, requiring the most skill? Ted Williams claimed it's hitting a major league pitcher. Maybe. It certainly is on my short list, based on experiences of playing baseball. These include batting against a pitching machine during the summer of 1973 (helping me win the first Anteater Olympiad) when I observed that hitting a medium-fast pitch (80 mph) was easy, but it became much more difficult when the speed increased to 90 mph, due to human limitations of reaction times plus swinging times. And it was “wow” at 100 mph. Many major league pitchers throw in the mid-to-high 90's, and instead of simple fastballs (like the machine) they throw fastballs that “move” a little, or a lot (often both sideways and down) with curve balls & sliders and sinkers. And unlike facing a predictable pitching machine, with human pitchers there also is a “fear factor” because a batter must be prepared to protect their bodies against a beanball (or elbow-ball, hip-ball, knee-ball) that's intentional or is just a wild pitch.

For many reasons, Ted Williams has a strong basis for his claim about baseball. But my choices would be quarterback (football) and point guard (basketball), especially when playing against skillful defenders at a high level (whether it's high school, college, or pros) due to the complexity of their situations (when deciding) and difficulty of their actions (when doing).

Although a quarterback usually is more important for their team, having a bigger impact on who wins a game – this is why so many top NFL Draft Picks are QB's – for aesthetic reasons I prefer the artistry of point guards, especially in their passing. Doing this well requires excellent “court vision” by knowing where the other 9 players are now and what they might be doing soon, plus “court intelligence” to quickly make wise decisions — among the many options for dribbling, shooting, or passing — and then doing skillful actions. Most of my favorite bb-players have been point guards; these include Earvin "Magic" Johnson for the ShowTime Lakers, and many others (including Steve Nash, Devin Harris from UW, Chris Paul) in NBA, and now Caitlin Clark in WNBA. { In addition, Caitlin's first year as a pro was especially fascinating because there was so much extra drama, both on-court and off-the-court. Unfortunately, much of the drama produced results that were negative (were detrimental to individuals, and to society as a whole) in many ways. I'm hoping-and-praying that people's actions will be less negative in the future, will be more positive so we are helping to “make things better” with problem solving that produces beneficial results. }

For a long time I've watched women's basketball, beginning in Iowa where high schools (even in small towns like Victor where I began K-12) had teams for girls, and a state tournament.

Much later at my second UW, in 2000 our women's team didn't make The Big Dance but were invited to “the small dance” of NIT, and all games were home games in Madison because we had loyal fans and high attendance. I watched the second round in Kohl Center, with UW winning 82-76. For the third round, in the Quarterfinals our coach (Jane Albright) suspended 7 players, including 2 starters. Some people thought she was noble-yet-foolish for living by her principles altruistically, despite realistically conceding the game. But the rest of the team came through and won. Then the entire team won their next two games, and the title. Although some cynics insultingly belittle an NIT Winner as “the 65th best team,” after winning multiple games the players (plus coaches & fans) know it's worth much more. / A few years later in 2007 the NIT Final was UW vs UW, with Wyoming — the only UW I never attended, with UW-FarWest in Seattle WA followed by UW-MidWest in Madison WI, but not UW-WildWest in Laramie WY — earning the victory on their home court (versus Wisconsin) and their winning ➞ immediate celebrating and continuing influence.

In some years I also watched Wisconsin's high school tournaments (boys & girls) on tv, and enjoyed both.

When watching games, often I'll focus on the actions of point guards who “help good things happen” for their team, and because it's one of the most difficult skills in sports.

Overcoming Obstacles in World-Class Barefoot Water Skiing

Here is an email I wrote for the students in a course (Chemistry in Society) taught at UW-Madison by a friend, Teresa Larson Jones:

You've seen Dr Larson “in action” during lectures. She also is impressive as a world-class competitor in a sport whose mere existence is surprising. Is it really possible that people can ski without skis? Yes, and on her bare feet she even does fancy tricks, slalom weaves, and jumps off a ramp. While being pulled across the water at over 40 miles/hour! Hanging on using a shoulder with a troubling and painful history.

You've seen Dr Larson “in action” during lectures. She also is impressive as a world-class competitor in a sport whose mere existence is surprising. Is it really possible that people can ski without skis? Yes, and on her bare feet she even does fancy tricks, slalom weaves, and jumps off a ramp. While being pulled across the water at over 40 miles/hour! Hanging on using a shoulder with a troubling and painful history.

You can read about this in a bio-page and series of 6 articles (that soon will become 8) with her inspirational reflections on a challenging medical-and-athletic journey during the past year. It's a fascinating “comeback story” about setting goals (like wanting to compete successfully in this summer's World Championships), adjusting goals and strategies, pursuing goals by investing intelligent hard work, maintaining an attitude of patience and perseverance when coping with unexpected setbacks, enjoying the process and the payoffs. In your own pursuit of personal goals, you also are motivated by wanting to “be all you can be” and achieve success.* I think you'll find that Dr Larson's attitudes and actions, in rehabilitation & athletics, can be applied in these areas of your life or (more likely) in other areas, including academics, in Chem 108 and your other courses.

* In the words of John Wooden, an all-time great coach who is one of my favorites, "Success is peace of mind, which is a direct result of self-satisfaction in knowing you made the effort to do your best to become the best that you are capable of becoming."

You can see her bio and a series of 8 articles (written while she was a featured athlete/writer for Athleta - about) where she tells a fascinating story of "Starting from Scratch" and "Building Momentum" that was stopped by a setback, then "Bouncing Back (Again)" in her battles with injuries & surgeries, so she could "Return to Competition" and "Shatter Glass Ceilings," but then face the emotional obstacle of "Post-Achievement Blues," and ending the year with an encouragement to "Choose Your Own Destiny."

updates: Since overcoming her major setbacks in 2012, Teresa Larson Jones (aka Teri) has continued performing well in high-level competitions for women, winning the Senior Barefoot World Championships in August 2016. Three years later, she continued earning high scores at age 50, with a Personal Record in Jump, and near-PR's in Slalom & Tricks. Two years after all competitions were covid-canceled in 2020, in 2022 she was the US National Open Champion (it's open for all ages, and she is the oldest to ever win this), had PR's or near-PR's in all events, was #1 in World Seniors (35 & older) and has decided to “retire on top” in good health. 🙂

REACTION TIMES

batting cage with baseball-pitching machine: In the summer of 1975, speeds of 60-70-80 mph were easy to hit, 90 was a challenge, and 100 was "wow" due to the short reaction time, even without curves or beanballs -- [[ Ted Williams claimed that most difficult athletic skill is major league hitter (against major league pitching with curves & sliders, changeups & fast balls, sinkers & beanballs) and his claim has some merit, but each sport requires different kinds of skills, with wide range & variety; my vote for most difficult is NFL QB because... (later i'll describe) ]]

similar colors (red vs almost-red): It was U of Illinois (in orange-red, home team) versus U of Wisconsin (red-red) in uniforms that looked very similar, especially when UW was required to make split-second decisions due to the full-court pressing defense of UI. How did this happen? Evidently UI sent UW an email saying “we'll wear our orangish-red road uniforms” but the UW staff (those responsible for making road trips go smoothly) didn't see it so they packed only their usual “road red” instead of white, then on game-day UI refused to change into their usual “home white” and the referees allowed the uniforms to be red vs almost-red, despite the disadvantage to UW.

multi-colors in ultimate frisbee: In the popular Madison Summer League, one year Team Discount (with two former housemates) started in C League, and won all games so they were moved up to B League. TD officially forfeited all games they would have played in-B before moving to B (from C) so in the playoff they always were seeded low (which was lower than deserved based on their skills) with the higher seed wearing white and lower seed wearing dark. This is typical (as in NCAA's March Madness where the higher seed always wears white) but... For other teams, every player was white, while players on Team Discount wore many different colors — green (Mike), black (Dave), maroon (Ashley), pink (Emily), orange (Shelby), and so on — and this made it easier for TD players to quickly (with fast reaction times) know who was in each part of the field, capable of being passed-to, so it was easier for TD players to make the quick decisions required by high-level players. Mainly for other reasons (but also helped by their colors) they beat the top seeds (2, 3, 1) and won the championship!

Colored Uniforms and Response Times: Here is more about the two paragraphs above. / In the basketball game with Illinois (orange-red) vs Wisconsin (red), IL was doing a full-court press (for parts of the game) so UW players had to make fast decisions. In most games the uniforms would have been highly contrasting, making it easier for UW to recognize the color and decide "if red pass to them" but "if white keep it away" so they could quickly make good decisions. But in this game all players were red(ish), causing a split-second delay in recognition for UW players (who were being pressed, so quick decisions were required) and this was a disadvantage for UW, and thus was an advantage for UI who was doing-the-pressing. / In football the home team usually chooses dark (partly to "look tough" but also for camouflage) vs basketball the home usually chooses white (at least in college) although this seems to be changing in NBA. / in Ultimate Frisbee, Team Discount had multiple colors. I asked Mike if this was beneficial and he said yes, giving a split second recognition of who it is, e.g. if Ashley he can predict that she will respond well (like skilled receiver "running route" in football) and he will lead her because he knows she will keep running fast, but others maybe not. On the higher-seeded teams (2 3 1) all players wore white, so they had no color-cues to help them quickly recognize each teammate; instead each player had to recognize "who it is" by facial/body characteristices, which was slower and less effective, compared with also seeing colors. I'm suprised there were no complaints from other teams, forcing Team Discount to all wear the same color, either all blue, or all green, all red,...

A person should say “I feel humbled” only when they actually have been. Instead, sometimes when a person receives an award (or wins a victory) they say “I am humbled by this honor.” Uh, no you weren't. Being truly humbled happens when you lose a game you should have won, or stumble and fall flat on your face (as in this race against The Freeze) or pee your pants on national tv. When you fail in a humiliating way. In these sad situations, you have a justifiable reason to feel humbled. But not when you're being honored for doing something well, or have won a victory. { In this page, two examples of being humbled are (major) Dan in Olympic Trials and (minor) me in football practices. }

a sad story for a world-class athlete:

In the 1992 USA Olympic Trials, Dan O'Brien (#1 in the world) was favored to win the Decathlon. He was leading the field after 7 of the 10 events, on his way to winning. But in the pole vault he “passed” at several lower heights, and then missed three times at the height he chose to begin, that he had “never missed” in the recent past, and was confident he wouldn't miss on this day, and overall he would be helped by conserving his energy for the final two events. But because he didn't succeed in clearing any height, he got zero points for pole vault, and fell far down in the standings. He didn't make the team. / comment: I think the US Olympic Committee was being rigidly stupid when they didn't “give him a break” because he was clearly best-in-the-world, despite his mistake in the Trials. In fact, Dave showed this by breaking the world record for Decathlon a couple of weeks after the Olympics that he was not allowed to compete in. But sadly, he never got a chance for this Olympic Gold. {although he did win a gold medal in the 1996 Olympics} The story is written up in many places, including a fascinating documentary in a 30-for-30 by ESPN about the "Dave and Dan" ad campaign and what happened to it.

a similar (but un-sad) experience for me:

Something like this happened to me but at a much lower level, with less to lose, and eventually nothing was lost because there was a happy ending. In high school, each year the track season for our league began with a "team day" in which scores from each event were added together to determine the winning team. {this was a little like adding the 10 scores of one athlete in a decathlon} Our team was expected to win a close battle, and I was our best high jumper, rated as "top two" in our league.* But for awhile it looked like I might fail, causing our team to lose many points. {but not all because our second-best jumper would get some points, although fewer.}

Why? After passing two lower heights, I missed twice at a starting height that (like Dave 26 years later) I "never missed." But this day I did miss. Twice. Before my third (and possibly final) attempt, a teammate gave me wise advice – do a short sprint – so my muscles would become accustomed to explosive effort (needed for jumping higher) and would be relaxed (helping my body "do what it knew how to do" with better technique, without interference from "too much thinking") – so I did this and (very fortunately) then cleared the bar on my third attempt, thus escaping failure, continuing on to get 1st place in the high jump, helping our team get 1st in the overall scoring. His advice helped me jump better on that day, and then throughout the whole season, and in future years.

btw, I developed a strategy of laying down and "looking up at the bar from the ground" so it seemed less-impossible when I was standing up and looking at the bar (6'2" in high school, then 6'7" later) that was above the top of my head. / Also, one time I unexpectedly landed flat onto the ground but wasn't injured, partly because I was relaxed (expecting to land on soft foam) instead of tense (waiting for the impact on hard asphalt). More generally, technical innovations (foam pads or air-filled pads, instead of the earlier sand or sawdust) allowed technique innovations (due to the now-softer landings) with a new style, the Fosbury Flop that was creatively pioneered a few years later.

* I was "top two in our league" and in 4 competitions we each won 2. But he won the most important, helping his team win the league championships with his 1st and my 2nd. Because of this, in the same day I helped our teams win one title and lose another. How? One factor in the 2nd place was my leg being less-jumpy than usual because I had played 4 sets of tennis earlier in the day. We were playing the 2nd-place team in the conference, and our coach wanted to be sure we clinched the League Championship so we would be invited into the CIF Playoffs. We did win that day, and later won a CIF Championship, as explained here. / I never questioned this decision – telling me "you must play 4 sets before jumping" – because he was giving me special treatment by letting me compete in two sports during the semester (previously never done in our high school, getting two simultaneous letters) and he knew I would choose tennis if he said "you must choose." Also, in his first year as my coach he strongly encouraged me (well, basically forced me) to change my backhand and the change made it much better; this was another reason for me to appreciate his coaching, to not question him during this day of two championships, with winning and losing. Later, in the first round of our playoff he said "don't play your 3rd or 4th set, we'll just forfeit the points if I know we'll clinch the victory." Our players won all of their first & second sets and then, after winning at least one more so our team had enough points to advance to the next round, he forfeited all of the remaining matches. We quickly got on the bus and drove back to our high school, where I jumped into our family car and drove to "the second level" of California's CIF Track Championships, arriving when the bar was at the maximum height I had ever cleared. Without warming up except for a short sprint (a lesson learned in my first event of the season, then used always, including this final event) I missed once and made it the second time, but didn't succeed at the next height, so didn't advance to the third level of CIF. But this wasn't due to the two sets of tennis, because even with totally fresh legs I wasn't capable of jumping high enough to advance. It was a good day for me, and earlier it also was good for our team, and later we continued onward to win the title!

Earlier I describe other stories I am writing, about exploring your own city & my respect for defensive halfbacks & teaching children (or dogs) and more. Below you'll see outlines with rough-draft ideas for some (but not all) of the content that will be here later. These ideas will continue being developed during late 2021.

Differences in Educational Empathy: Teaching Kids and Teaching Dogs Teaching Kids (instead of Adults) In the 1980s when — after learning how to juggle in 12 years and 45 minutes — I taught juggling classes (beginning & intermediate) in Seattle for UW's Experimental College, almost all of my students were adults, so I developed teaching methods that worked well for them. [==] But one time I taught for Seattle YMCA, in a class that included some students who were young (8-11 years old), and I discovered that some of my teaching methods did not transfer well from adults to children. In a beginning class with adults, in a progression-of-learning I asked them to "do things" with an increasing number of beanbags, with 0 and 1, then 2 (the key step) before juggling with 3. After we quickly moved thru 0 (with just hand motions) and 1 (using these hand motions to toss a bag from one hand to the other), I showed them the movements they'll do for 2 bags, then put their action "on pause" for a minute so I could explain why a familiar habit should not be used for juggling. In sports, when you catch a ball you can improve your eye-hand coordination if you "watch the ball" until you catch it. This works well if there is one ball. But when juggling 3 balls it's impossible. To show why, I juggle 3 bean-bags while whipping my head back & forth trying to watch every bag all the way, and it's obvious why this cannot be done, so it should not be attempted. Then I explain what to do instead, by letting your eyes-and-brain naturally "make mental movies" of what a bag is doing, of where it is and where it's going. I show this by throwing a bag, closing my eyes thru most of the throw, and catching it, which is possible because my brain-and-hand "know" where the bag will be (and my hand moves to that location so I can catch it) because eye/brain/hand coordination is based on mental movies. The eye/brain/hand of every person (not just an experienced juggler) can do this, and your skill in doing it will improve with practice. All of this (about mental movies) takes about a minute, and in previous classes the adults waited patiently until I said "now you do it." But the kids wouldn't wait, instead they started "doing it" without waiting for me to explain the ideas that, in the long run, would help them improve more quickly than they could without these ideas. I didn't anticipate this reaction from the kids, and I didn't plan "what to do" to avoid it. I had empathy for adults — based on my intuitions as a fellow adult, plus experience from previous classes where the "mental movies interlude" worked well — but had less empathy for children, so I didn't expect their response, and didn't plan for it. Later, between the first class and second class, I thought about what happened, tried to understand (with empathy) the childrens' point of view, and adjusted my lesson plan, but I still never overcame the gap between my skills in teaching adults (excellent) and teaching children (mediocre).

Teaching Dogs (instead of People) In early 2019 [when this paragraph was written] I'm trying to improve my empathy for dogs, especially for our Zoe, whose name means "life" in Greek. She is full of life, mostly in good ways, but... she is over-exuberant when meeting new people (and other dogs), and this hinders her from "getting what she wants" because her behavior makes it more difficult for people (or dogs) to interact with her in a loving way, and (especially for small children) without injuries. If I had better dog-empathy I would know Zoe better, would understand why she behaves this way, and what I can do (as a teacher) to help her change her behavior so her quality-of-life will improve with better relationships, so she can get more of the good things (affection from people, playing with dogs,...) she wants. But still allow her joyful enthusiasm. In an effort to improve my empathy-for-dogs, I'm taking a class taught by Khara Knight, whose philosophy of teaching is built on a foundation of..... [ iou – eventually this will be continued, although now things are very different for Zoe in her new home! ]

Thrill and Agony -- ABC's Thrill of Victory and Agony of Defeat. examples: WI-Duke (imo) 2015, Gonzaga(s), Virginia in 2018 (a never-before failure of 1-seed in 1st round) followed by 2019 (national championship), the comeback-year of Jennifer Capriati (going from high to low to high-again), my watermelon-eating photo finish (when after I saw the winner celebrating with his buddies, I was happy that I lost because I often cheer for the team/person who will feel the most joy if they win, or most sorrow if they lose, and it was him, not me); women's tennis-final 2018,... [to be continued]

my Tennis versus my Juggling: differences in my quality for Teaching and Performing, Teaching: There were big differences between my teaching of tennis and juggling. My self-evaluation (and I'm sure the students would agree) is that as a tennis teacher I was unskilled and ineffective. How? In many ways. I was not very effective at making it fun for students (with attitude & activities), or providing a class structure (mixing “drills” & playing, plus talking), or analysis-and-guiding with “tips for improving”, or even providing a non-analytical “inner game” approach (i.e. without external directing-with-instructions, instead by directing student's attention to their own observing to stimulate sub-conscious internal self-correcting) that I later learned to appreciate. But when I taught juggling, all aspects of my teaching improved. Why? • age and experience: I taught juggling when I was older, had more experience, knowledge, confidence. Tennis was my first teaching at ages 17,18, and 22, without much improving. Then after more experiences with teaching-and-life, I taught juggling from 31 to 41. / But this wasn't the only difference, and even now when teaching tennis I would feel less comfortable (and would have less skill) compared with my comfy-and-skillful teaching of juggling (although more for adults than with children), and part of the reason is due to... Performing(s): Ironically, my public performing was better with tennis. In both tennis & juggling, I was fairly skilled (although not elite level)* technically in private performing. I learned each skill quickly, then improved rapidly; e.g. you can see some skills in my juggling video made at age-60, although my skills had decreased since age-35 when I could juggle 7 balls (which is MUCH more difficult than 3, 4, or 5) and do tricks more fluently & reliably. But in public TENNIS GAMES my competitive performance was consistently at a high level, was limited mainly by my level of skill — i.e. I rarely lost when I should have won, typically losing when the other player had superior skills, and sometimes (but not usually) when our skills were similar — rather than my level of performing. By contrast, in public my JUGGLING SHOWS (on the street or stage) were not very entertaining or impressive or profitable or (for me & viewers) emotionally satisfying, with my level-of-performing far below my level-of-skills. {also: How my high school coach forced me to change my backhand so I could improve it and help our team win a championship in SoCal; and learning more from experience – learning from ALL experience whether it's failure or success – in welding and in other areas of life, by a shifting of metacognitive regulation for achieving goals of learning and/or performing and/or enjoying. } * Typically I was a medium-big fish in medium-small ponds.

• my learning times: Why did my process-of-learning take a long time (12 years and 45 minutes) for juggling, but only a short time (5 seconds) for swimming? After you think about this for awhile, read some clues. / And for learning to ski, it was a medium-short time during a morning (when it was frustrating with ineffective futility) plus afternoon (satisfying with effective learning).

watching sunsets One of my favorite times was Summer 1996, sitting on a dock with a 210-degree view almost down to the horizon of Lake Mendota in Madison, with sunset sky colors (blue, pink, orange) reflecting off the rippling surface of the water. / Beautiful sunsets require clouds that "reflect light without smothering" so I set a daily alarm and observed the clouds, to decide whether it would be worthwhile to view from the nearby dock. earlier — During my senior year at UC Irvine, Fall Quarter 1969, friendly neighbors gathered to watch sunsets from the west-facing balconies of our student apartments. later — In a 5-ticket lottery, Mom and I won a wonderful new dog (our fluffy-and-joyful “life dog” Zoe) in mid-November 2018. During walks with Zoe it was a season of beautiful sunsets — due to the clouds that formed (during that time of year in Anaheim CA) in much of the sky, with “the right kind of clouds” for light to reflect from, but not enough cloudiness to smother the colors — sometimes with 360° full-surrounding beauty, seeing sunset-colored clouds in every direction. The sunsets had wide variety, including this one:

joyfully returning to Madison (after 7 years away) in 2020 with a different situation, living in a different location. above, my respect for defensive halfbacks (based on my own playing), and Watching a Linebacker

clues about two of my times-for-learning: For juggling, you've probably realized that the time-to-learn occurred in two phases. What do you think happened during each phase, and in-between? { it's described in my page for Do-It-Yourself Juggling about a class I taught for a decade in Seattle – my first UW City – plus links to videos of skillful-and-funny Flying Karamazov Brothers, because one brother was part of my process, and they're fun to watch! } For swimming, my fast mental learning (happening in a few seconds) allowed the slower physical learning that followed. What happened? (i.e. what did I learn mentally?) — spoiler alert: If you want to think about this question, and imagine what happened, think about this first before you read the story of my experience or even read the rest of this paragraph. / here is another clue about what I learned and how: I had a science experience, a scientific reality check that falsified my theory about “what happens to my body when it's in water.”

watching snow and seeing wind Near the end of winter in March 2012, thinking “I might not see snow again for awhile” — and this was true, with no in-person snow from Spring 2012 until December 2020, almost 9 years — I invested 45 minutes to walk around the neighborhood (between my apartment and Union South, a block away) and just watch the snow. At one special location, the invisible wind “became visible” due to a street light illuminating the snow swirling in the wind, up & down, sideways, traveling in different ways at different distances away; I could see it (the snow in external vision, and thus the wind in my internal vision) moving in one direction at one distance, but a little closer (or further) it would be moving in other directions. It was Natural Art-in-Motion. Earlier, in 1989 (my first winter in Madison) watching from the balcony of White Hall overlooking its u-shaped courtyard, I was thrilled by the beauty of wind-and-snow in motion. Earlier, beginning in 1970, I watched snow (for the first time since Iowa in 1961) swirling under a streetlight in Seattle, and in other locations (courtyards,...) around the city, for most winters until Summer 1989 when I moved to my second UW City.

playing in the snow In the 1970s in Seattle – my first real city (by contrast with the suburban megalopolis of Orange County and most other parts of SoCal) and first UW City – every time it snowed we thought “it might be the last time this winter” so people (especially in the student area where I lived, near fraternities & sororities) would go out and play in the snow (with snowball fights, building snowmen, making snow angels,... just playing) and I would watch them, and watch the snow-and-wind in streetlights, courtyards,... One of the times I joined in the fun, when they were sliding down a short-yet-steep hill across the street from my apartment. It was hard-packed snow, made very slick by our many descents. Some of us stood up and slid down on our shoes. At first I just tried to survive, to stay on my feet until the bottom. After awhile I became more adventurous, including 360° spins, usually 3-5 per trip with alternating directions; I did about 40 total, with only a few minor falls. Then I was surprised by an almost-instantaneous “wham” fall, with no control by me. Fortunately my body was ok, but it was a shock to my emotions. I thought “landing on one side of my butt was ok, but it could have been my tailbone” and I imagined full-body paralysis, instantly becoming a crippled quadriplegic in my early-30's. Not a fun life. That was my last run down the hill. driving in the snow — Later I'll share some details about... hearing stories of dangerous "black ice" from a housemate when first arriving in Seattle; someone told me about seeing on-and-off "strobe" headlights during an east coast evening (can you imagine why?) due to black ice; my fun trip to "play with my car's handling" in a safe parking lot (almost empty at night) of UW-Seattle, that turned dangerous-and-scary when new snow began falling and the roads became slick, when back on 45th (a main street) I survived a downhill block with stop-light at the bottom of 11th Ave, turned onto this major street where I should have stayed until finding a parking spot, but instead I foolishly decided to turn right onto a small street with an uphill block, then my car started drifting sideways (due to tires spinning despite my fairly skillful use of gears & clutch in my 4-speed Mustang) and my vividly scary imagining of the car drifting sideways into a line of parked cars, sideswiping each on its way back downward to the major street, causing major damage to those cars and my driving record & insurance premiums, but then... a welcome rescue! when a stranger decided to help me, and I felt him/her begin pushing enough (it didn't require much) that my wheels stopped spinning, so the car began moving forward to the top of the hill, and with a huge sigh of relief I turned onto 12th Ave (a major street) and found a parking spot, waiting until the next day (when roads were safe) to move the car and avoid getting a ticket in the "2-hour zones" on the major street. I never did get a chance to thank my rescuer, but I remain very thankful for their help. decisions about driving in snow: When my father was superintendent of a district (North Mahaska, with three small towns) in Iowa thru 4 winters, sometimes he had to decide whether to "call it off" for a Snow Day, with pros & cons and real consequences (they were certain-and-actual for saying Yes, were possible-and-imagined for saying No), so he stayed awake thru much of the night getting reports (about the snowing & drifting, quality of roads, estimates of safety or whether a bus could even travel a whole route,...) and he mentally-emotionally processed the info so he could make a wise decision. Each time there was a heavy snow, it was an ordeal for him. / But each of these was less of an ordeal than earlier in life during World War 2 when he was the co-pilot (and sometimes pilot) for a B-24, when his crew survived 30 dangerous missions, each having a significant possibility of ending with their deaths. He wrote about these war experiences, and many other experiences (by him & others), in a book that was a great gift for his family. riding in the snow — in Seattle (a little) and then Madison (a lot); Although in Seattle I rode my bikes (1-speed, 3-speed, 10-speed) thru many kinds of snow, usually this was only when roads or sidewalks were snow-free bare and therefore safe. But shortly after arriving in Madison, I wisely decided to buy a 21-speed mountain bike and use 2" tires with snow-gripping tread; { i also bought a used 10-speed with thinner wheels-and-tires for faster rides when there was no snow }; some stories that later I'll develop (with details) are... "playing in the snow" one evening my first year by doing fishtails-etc in an empty paved space; being able to plow thru 15" of lightweight snow during the afternoon of a 20" snowfall day, early in the second winter, Dec 1990; but later in the year being stopped by 5" of dense heavier-wetter snow; my "3 low" strategies for snow – lower gears, lower speeds, and (most important) lower seat-height so when the bike fell over (frequently) I landed on my feet instead of (rarely) on my hips-knees-elbows during a dump-crash; I had 7 dumps in my first 5 years (with clear memories of five, re: when-where I was, why it happened, etc) despite having a lower seat, but then had no dumps in the next 18 winters in Madison; snow is usually ok so I can ride the bike with control, but ice is tricky, can be dangerous, so I wondered whether to get studded tires, but never got any; and more. climate shocks — While growing up in Iowa, the winters were cold. For three years I had a paper route, therefore often walked long distances outdoors in the cold, when being indoors would have been much more warm, comfortable, enjoyable. Then at 14 our family moved to Anaheim CA, with much milder winters. From 1970-1989 it was mostly the northwest in Seattle,* and occasionally Eugene or Corvallis in Oregon, with temperatures that were occasionally cool but rarely cold. / But sometimes it's very cold in Madison. The night before my first trip back to our family home in Anaheim CA, I was riding 15 mph into a 15 mph headwind with air at -20°, for windchill below -50°, so I could print-and-deliver (thru a mail slot) my last paper of the semester; almost all of me was covered up, including goggles (used when teaching chemistry labs) plus a face mask & scarf, but my nose was uncovered so after arriving at UW I worried that if I touched my nose it would shatter (like a rose petal or racketball frozen in liquid nitrogen) but I never tried this experiment, didn't want to take the chance, so I'll never know. It felt good to be indoors at UW, and even better when I returned home afterward. The next evening I walked off the plane in Orange County, CA, greeted at 7pm by 70° air, and oh it felt so good to be outdoors and warm! / Later the Reverse Climate Shock, from warm California to cold Wisconsin, actually felt ok. This was partly because I was expecting it, and also because I was looking forward to the cold ending with springtime in a couple of months, and occasionally even earlier with short-time breaks from the extreme cold. temperature expectations -- in Madison, 65 in August feels cold, but 65 in March feels warm, in fact 45 in February "feels warm" compared with the typical "highs" (of sub-zero thru 20's) in earlier wintertime. temperature + wet/dry -- 45 & wet (frequent in Seattle for a bike rider) "feels colder" than 0 & dry (in Madison if dressed well) -- so after a few mistakes of not-planning, I learned the lesson (yes, it should have been obvious before the first ride) of bringing dry socks to put on after a bike ride in rain; I had many experiences of contrast between the cold misery of being wet after riding away from home, versus the comfy relief after riding back to home where it's warm and I can exchange wet clothing for dry clothing, for all clothing instead of just socks.

is second place OK? Sometimes. In sports, some of my favorite moments were second places. But sometimes it's very disappointing to finish second or lower. And sometimes athletes respond in strange ways, as in the 1996 Olympics when (in my opinion) Carl Lewis made a fool of himself by making unwise decisions, with motivations and "logic" that were totally foreign to me then, and even now I still cannot understand. The most foolish decision was before the competitive events began, and this was followed by more mistakes between two events, his own long jump and his country's 400m relay. In a surprise for everyone, Lewis won the long jump, and this gave him a 9th gold medal, the most in olympic history. But with a motivational strangeness that makes his actions much more difficult to understand, his win put him into "a tie for first place among fellow athletes (all with 9 golds) who competed in different sports at different times" so they were not in head-to-head competition with Carl. He didn't want to simply win (or not-lose) a competition, which would be understandable for an elite athlete. What did he want? He wanted to "take their names out of the record book" instead of just "putting his name into the record book" (it already was in); and this makes the actions by Lewis seem even more-silly, less-understandable. One of the worst parts of his unwise decisions was putting pressure on the coach for the 4x100, trying to persuade him to abandon the principles that were clear when Lewis was recruited for the team, that you cannot be in the relay unless you attend the camp; Lewis chose to skip the camp, so the coach did what he said, by not letting Lewis run on the team, which lost – in large part due to the poor performance of the runner who ran instead of Lewis, who had trouble with the baton-passes, and although certainly "trying hard" this can (ironically but realistically) make a sprinter run slower, because optimal relaxation — by activating only the muscles that will help you run faster, and relaxing the muscles that if activated would make you run slower — is necessary for maximum speed. / I thought the coach did the right thing, and Lewis (plus tv announcers who mainly "took the side of Lewis") did the wrong thing. / Bill Lyon (in 1996) agreed, and I like his explanation. And before the race a member of the 4x100 team agreed. { iou – later, motivated by this fascinating story, I'll find other articles & videos.} Here is how I think Lewis should have been thinking, before the competitions began: If I win one more gold medal, I'll be in the record books, tied for the most-ever golds. I'm much more likely to get gold in the 4x100 relay, so I'll go to the "training camp" for this relay, and (probably) I'll get gold for that event. Then after unexpectedly winning the long jump he could have thought, altruistically, "I'm in the record books, tied for most-ever gold, and – because I want to be generous, thoughtful, kind, with empathy – I want all of our names to remain in the record book" so I'll skip the relay, instead of selfishly thinking "I want to remove the names of all other 9-time winners." Or, more likely, he honorably could have thought "I'll do the relay because I've trained for it in the camp, and my coach & team (+ country) is expecting-and-wanting me to participate, so I'll do it and will try to help us win." As described above, although “first place” can be satisfying, for me it usually isn't an essential part of satisfaction. For example, music is so wonderful that I've had lots of fun with it despite being just a moderately-skilled musician. My early experiences were listening to music on the radio, and with our family's collection of vinyl records. Then I began playing pre-composed music with trombone in school bands, 5th grade thru high school, in Iowa and Anaheim CA, where it was fun being... a small fish in a big pond: Our family's move upgraded me from one of the worst junior high bands (in small-town Iowa) to one of the best high school bands (in big-time California). Loara HS began in 1962 with only 10th graders, then added 11th & 12th in the next two years. I began in 1963, and was a small fish (just one of the Second Trombones, playing “good enough to be on our excellent band team” but not great, being sufficient but not excellent)* in a big pond, in our magnificent band. Fall Semesters, we played in street parades & football shows, placing high in all competitions (in SoCal where the quality of marching bands was very high) and winning some. Spring Semesters, we played concert music. Our teacher & band director (Rick Marino) was creative, dynamic, and disciplined, helping us develop individually & collectively. In 1968, Loara won the prestigious All Western Band Review (biggest parade-event on the West Coast), playing Purple Carnival – a beautiful march that's one of my favorite songs. Being a small part of our band's big success – while I was at Loara, and in later classes who built on what we had begun – was very satisfying. { a longer history of "having fun with music," focusing on improvisation } * A similar experience was being non-excellent but “good enough to be on our excellent football team, although not good enough to make it a main reason for our excellence,” and their graciousness (in letting me play) allowed me to help us win the championship while learning respect for defensive backs.

learning how to swim in 5 seconds: During early-life swimming lessons, an inexperienced instructor (a teenage girl who wasn't “fat” but had enough body fat to easily float horizontally) told me to float on my back, saying “if you just just relax, you will float.” But I (a skinny young boy with much less body fat) could feel myself becoming un-horizontal (with feet sinking) and sinking. She didn't do any of the many things that a skillful instructor would have done to help me, so I decided “I can't float so I can't swim, this isn't fun, I don't want to do it, and I won't.” A few years later during a summer camp, I was in the water telling a friend “I can't float, so I can't swim,” but he said “of course you can float, everyone floats” and to prove it he told me to take a deep breath, then (in chest-deep water) grab my knees and curl up into the shape of a ball. When I did this, my observations — when first I sank (as predicted), but then unexpectedly (in a failed Reality Check for my theory about floating) I bobbed up to the surface — caused a radical change in the way I was thinking about my body's behavior in water, and the possibility of swimming. Probably you can guess what happened, in my thinking and in the water. My problem with not-swimming had been mental, not physical, and that 5 seconds changed me mentally. Later that summer I physically learned how to swim, especially with overarm side-stroke and backstroke, after starting with the bottom-line survival skill of treading water. A few years later, after my family's move from Iowa to Anaheim CA, I was excited to be swimming in the Pacific Ocean at Newport Beach, being pummeled by 15-foot waves, feeling like a shirt being tossed in a washing machine, without control but without drowning because I could hold my breath for a long time. In this California-situation, although fear was justified (due to the real danger of drowning) I wasn't afraid — well, I was afraid but overcame it and did enter the wild water of the dangerous deep ocean — by contrast with earlier Iowa-situations when I was afraid without justification (because in reality there was very little danger) and didn't enter the calm water of the safe shallow pool. Eventually I may share my story of an important benefit arising from the early swim instructor(s), when delayed effects of their incompetence — initially negative but later allowing the positive effects of my recovery during the insightful 5 seconds, then learning to swim — immunized me emotionally & cognitively, so I've never again felt the despair (felt by too many of us) that we hear ("I'm sinking all alone... gonna kiss this world good-bye") in a beautiful-yet-sad song, Cool River.